On November 25, I was one the three people who argued for the motion “This House Would Move Beyond Meat” at a debate hosted by the Oxford Union. The other two were Heather Mills, a vegan activist and businesswoman who has helped to develop a variety of plant-based foods and is trying to create a vegan industrial park in England, and Professor Jeff McMahan White's Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Oxford.

The debaters for the motion “This House Would Move Beyond Meat”: Jeff McMahan, myself, and Heather Mills.

Heather spoke first, describing the healthiness of a vegan diet, and the kinds of foods she is developing. Jeff described basic ethical arguments against eating meat grounded on moral claims about the well-being and interests of animals. After each person spoke for the motion, the debaters against the motion spoke. After two debaters spoke for and against, members of the audience were allowed to share their views in a two-minutes presentation.

Then it was my turn. As you are only allowed to speak for 10 minutes, I had practiced what I was going to say with two friends, Oxford-based novelist Helen McGregor and Christoper Sebastian who helped me whittle my ideas down, one hundred words there, another fifty words there.

The minute I began, there was a voluble reaction—gasps, laughter, heckling. I was startled. I thought I would at least get into the talk a little before there would be such a reaction. But as Sebastian said later, you could bury your expectations in a grave in a cemetery and you still wouldn’t have lowered them enough. Helen described the reaction over the 9 minute time period during which I talked as “heckling and ridicule and Bullingdon Club nastiness.”

Here’s what I said that caused the reactions:

_______________________________________________________________

What we choose to eat has consequences far beyond the circumference of our plates. Specifically, your vote tonight expresses our allegiance to or rejection of a white supremacist patriarchal worldview. Do we vote to further inequality and sustain world destroying violence?

In The Sexual Politics of Meat, I introduced the concept of animals as absent referents. In order to be eaten, animals must disappear as living beings—that is, be killed. They then disappear conceptually, as so many of the forms in which we eat animals’ corpses are massaged by euphemistic language: hamburger, steak, pork, bacon, etc. Meat eaters order “leg of lamb” not a baby lamb’s leg. The animals cannot possess their own body parts.

Tonight think about how the language of our debate has or has not participated in this structure of the absent referent. Who disappears and why?

21st century animal eating requires our complicity in a new colonialism. We know how settler colonization worked— “an erase and replace” system that forced Indigenous people off the land, replacing them with cattle and white settlers.

One of the defining aspects of the colonial legacy is an ongoing white supremacist belief system and an ownership paradigm. When you own land, you get the title to it. Entitlement and ownership are linked.

All the justifications for taking of the land by white colonial authorities included the claim, “well the Indians can’t prove they own the land.”

Hunting exists within this colonial ownership paradigm. It presumes that animals don’t have title to their own lives; once dispossessed of their lives, the hunted animal can become your property.

Approximately 90% of Native Americans were killed off by erase and replace settler colonialism.

It’s the new colonialism that boasts, “I’ll hunt for myself and be grateful like the Native Americans” as well as “I thank the animals for their sacrifice.” To which I have been known to respond, “how do you know the animal would have picked you to feed off their corpse?” The argument that hunting is ethical presumes that some primeval form of eating exists unmediated by the corrupting influences of society. There’s no room in the new colonialism for an Indigenous world view to exist, instead it collapses more than 100 Native American nations into one amalgam, and attributes a static indigenous worldview that erases those nations that were predominantly vegetarian and lived in urban areas. The new colonialists see nothing wrong with a pick-and-choose approach to Indigenous thought that never engages with the survival issues Indigenous peoples are facing.

Seventy percent of the population would have to be eliminated for people to rely on hunting. Who would live and who dies and who decides?

At the Oxford Union debate, Carol arguing for the motion.

When my partner Bruce, who stayed in the States with our rescued dogs, heard about the heckling he suspected that made me more impassioned and determined. He knows me well!

As for domesticated animals, Percy Shelley pointed out just after being expelled from Oxford, "the quantity of nutritious vegetable matter, consumed in fattening the carcase of an ox, would afford ten times the sustenance if gathered immediately from the bosom of the earth.” Two hundred years after Shelley wrote, one third of the land mass of the world is committed to animal agriculture. Entire ecosystems are disappearing. 80% of deforested acres in the Amazon were cleared for animal-based cattle grazing. So called free range animals contribute more greenhouse gases; while killing them in mobile slaughterhouses requires more water than industrial slaughterhouses, and leaves behind an immense amount of waste, requiring an intense amount of chemicals in the process. Your “meat” may be organic, but your slaughtering isn’t.

If you eat animals, you take up more climate space—requiring more water, more land, more forest deforestation, contributing more greenhouse gases. This is felt disproportionately by countries in the Global South. Their carbon footprint is smaller but they experience more frequent and intense climate-change-caused weather events; hese events especially affect girls and young women, so you get some misogyny along with your hamburger. The Western world colonized their space without sending a single beefeater.

Through colonial power the diet of beef-loving English people became normative. The food heritage of pre-Conquest peoples, like the land itself, was overrun. It was the colonizers, especially the British, who declared that the virility of the meat eating nations explained their success over the supposed feminine and weak “rice-eating” countries they defeated.

Historically, the vast majority of the world lived without animal protein as a central part of their diet. The assumption that the “best protein” is from corpses is a racist belief as it erases and replaces indigenous, African, Asian, Meso-American cultural food practices.

Meat eating is one of the ways gender-based structures of oppression are perpetuated. Men are taunted to renew their man card by eating meat because that’s what real men do—that’s the sexual politics of meat and it reveals how unsettled masculinity really is. Back home my library card is good for seven years, but a man card can expire between breakfast and lunch if someone eats a veggie burger? Masculinity—a construct of the gender binary facing constant destabilization—feels always under threat and eating animals is its protection racket.

That’s why, after 9/11, a focus on men as heroes and on meat eating became part of the reclamation of a wounded masculinity. When a Black man was elected as U.S. President, we saw how white this wounded-masculinity was. White supremacists weaponized eating meat, eggs, and dairy. Images of milk-drinking white men, of platters groaning with meat, and the baiting of liberal men as “soy boys” are all a part of neo-Nazi messaging. This is their right; this is their identity.

The new colonization rests on the unstable foundation of white men’s insecurities.

Look at the way people, er men?, in the animal industry speak of female animals as willing and ready to be made forcibly pregnant which female animals are powerless to resist. Yet popular culture is flooded with references to sexy cows, sexy pigs, sexy chickens, sexy fishes who all just want to have fun. They wantto be pregnant. And they want to be killed. Because this feminized sexuality wants to be eaten. The only desire animals are credited with possessing is the desire to be consumed, which strangely can only be expressed after their death.

Real life tells a different story: animals try to escape, from slaughterhouses, or farms; when able, cows try to reclaim their calves, taken from them so that their nursing material goes to human consumers. They fight and resist the fate the colonial empire claims is their welcomed destiny.

Some meat eaters are afraid of what they will feel if they look too closely at the degradations that constitute animals’ experience. Mention disabling practices or the devastating separation of cows and their babies and we hear meat eaters exclaim, “Don’t tell me!”

Why are they afraid of the feelings such knowledge produces? They accept a patriarchal construct that views feelings as unruly and untrustworthy. To say you care about animals is considered a sign of weakness in a world still committed to the gender binary that values stereotyped masculine “reason” over the stereotyped feminine “feeling.”

And yet the reasons we hear are so irrational!

“If I didn’t eat animals, they never would be born.” Meat eaters, like antiabortionists, have forgotten that one quality of nonexistence is not having awareness about existence.

Meat eaters say, “why if we put prisoners to work in slaughterhouses in England, they will be learning a skill.” I did not know that killing was a skill generalizable to other jobs.

The new colonialist boasts, “I only eat meat from locally-owned farms; and I know the farmers there love their animals.” If killing what one loves is standard practice, I hope they don’t start loving me.

“What about carrots?” we are asked, though I’ve never seen a meat eater leap into the road to save a carrot from being run over by an automobile.

When all else fails, meat eaters assert that animals are not our equals. One would think such inequality would require us to respond more, not less, sympathetically.

Meat eaters tell me it’s so hard to change, and yet I watch them work even harder not to change.

Is our global outcome to be determined by people afraid to change?

Change may be hard, but not changing is harder.

If you all agree that 95% of meat consumed is from factory farmed animals and that is wrong, then tomorrow chose the vegan option at your colleges—I know each college offers them.

Tonight, you are being asked to vote on whether you accept this new colonialism or not. Our menu choices don’t stay on the plate. Your vote tonight is important, but even more important is the question of what, or who, will be on your plate in the morning.

Sweet dreams.

____________________________________________________________________

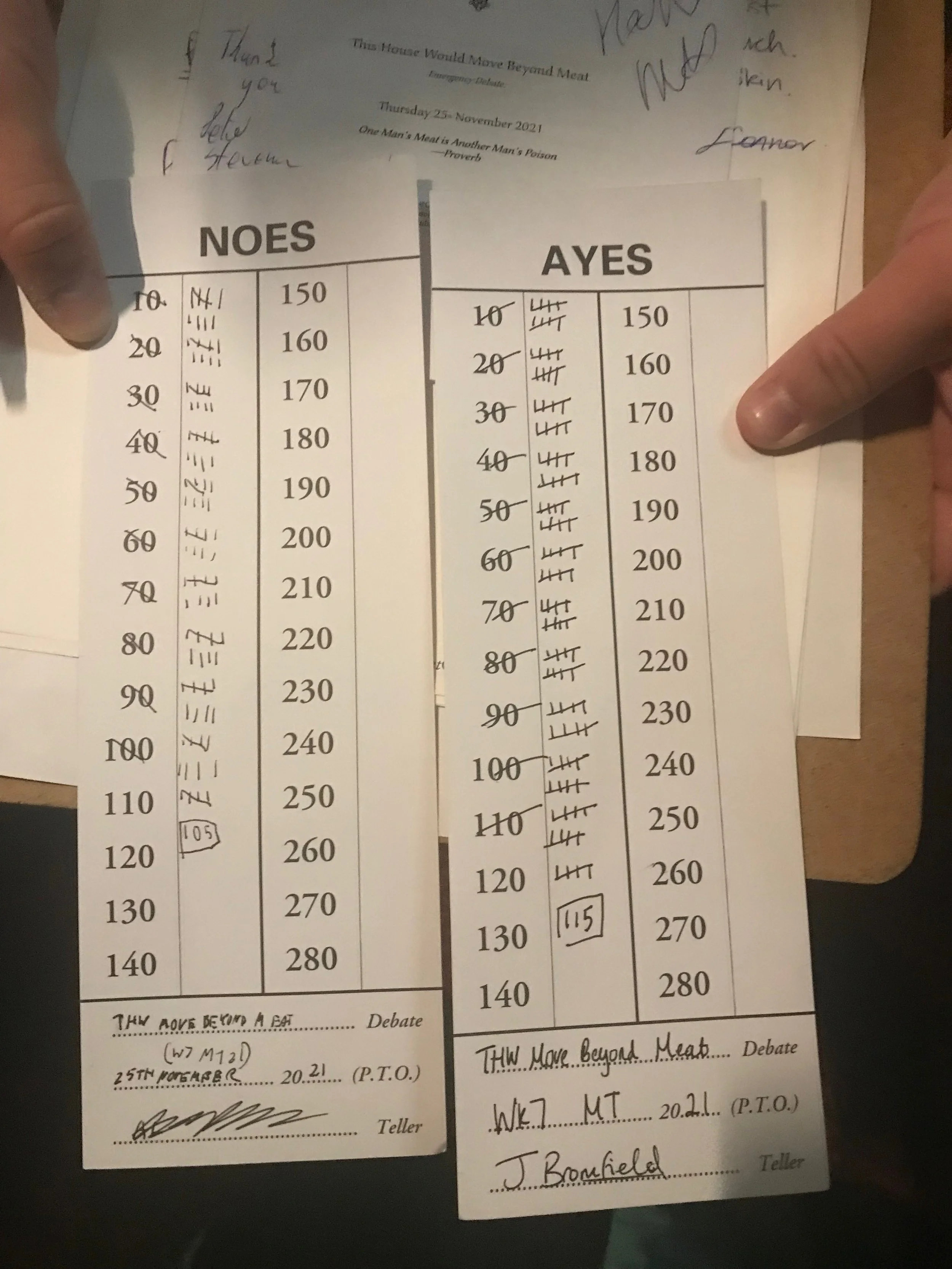

The Ayes Have It

The record of the votes at the Oxford Union’s debate: “This House Would Move Beyond Meat.” Despite—or maybe because of—the heckling, we won 115-105.

A very happy trio in the Oxford Union’s Gladstone Room, after the debate results were announced. Helen McGregor, yours truly, and Christopher Sebastian. I am so thankful for their support throughout the day.